BRICS and B&R are interrelated, as both are major initiatives based on developing economies, but nevertheless each has distinct features. The BRICS summit therefore provides an appropriate opportunity to objectively analyse the real weight and dynamics of the BRICS grouping in the world economy. Its significance is made particularly clear by making a comparison of BRICS to the G7 group of advanced economies.

To assess the real weight within the development of the global economy of BRICS it is useful to use the IMF’s projections for the current five years growth in the world economy up to 2021. Use of this IMF data does not necessarily imply accepting that all the details of the forecast are correct. But:

- First, the IMF is a bastion of Western economic orthodoxy and cannot be accused of producing data artificially favourable to China,

- Second, as will be analysed, the BRICS and G7 economies are so large, and their dynamics so well defined, that in most cases the broad parameters of their impact on world growth are unlikely to be affected by any plausible divergences from IMF forecasts.

More detailed points regarding the IMF projections are analysed below.

The concentration of the world economy

To form a clear picture of the overall significance of the BRICS and G7 groupings it is necessary to grasp the extreme concentration of the world economy in a few countries – this crucial economic fact is sometimes obscured by the different political one that there are more than 200 countries in the world each of which is entitled to respect. To show this this extraordinary concentration of the world economy in a few states it should be noted:

- In 2016, at current exchange rates, a mere five economies account for 54% of world GDP, 10 economies for 67% of world GDP and 20 economies for over 80% of world GDP.

- Measured in purchasing power parities (PPPs) the concentration of the world economy is only fractionally less. Measured in PPPs the top five economies accounted for 48% of world GDP, 10 economies for 61%, and 20 economies for 76%.

- Economic growth is more concentrated still. As analysed below, the IMF projects that the majority of world economic growth in the coming five years will be accounted for by only three countries – China, the US and India. These three economies will account for 54% of world growth measured at current exchange rates and 52% measured in PPPs.

The result of such extreme concentration of the world economy in a small number of states is that extremely rapid growth in a country outside the small group of the largest economies will produce desirable increases in living standards for that country’s inhabitants but it will not substantially affect overall global growth. To show this clearly, the two economies with a population of more than five million which have grown most rapidly since 2007, the last year before the international financial crisis, were Ethiopia, with annual average growth of 10.0% and Turkmenistan, with annual average growth of 9.8%. This produced considerable improvements in the economic position of both countries, but together Ethiopia and Turkmenistan accounted for only a marginal 0.4% of world growth whether measured at current exchange rates or in PPPs.

In summary, given the world economy is overwhelmingly dominated by a small number of large economies it is clearly of crucial significance that BRICS and the G7 combined include 11 out of the 20 largest economies – four in BRICS and seven in the G7. The really crucial character of BRICS and the G7 is therefore clear.

- BRICS is overwhelmingly the most important summit grouping of developing economies,

- The G7 is overwhelmingly the most important summit grouping of advanced economies

The upcoming BRICS summit is therefore in a crucial sense a parallel to the G7 summit. The relation of both groupings to the G20, which brings together both advanced and developing economies, and the issue of whether BRICS and the G7 between them fail to include any economies which are crucial for global economic development are considered below.

Speed of development

This fact that a very small number of very large states entirely dominate the global economy is crucial because it immediately removes a misunderstanding concerning BRICS – the misunderstanding that they are primarily important because they are rapidly growing economies.

As is well know, the original term BRIC was put forward by Jim O’Neill, who at the time the term was coined was Chief Economist of Goldman Sachs. Others, wrongly believing that the global impact of O’Neill’s term was merely an example of his skill in coining a good name, have made attempts to propose other groups of economies to replace the original term BRIC. All the failed for reasons which become clear when the real significance of the BRICS are understood.

For example the Financial Times, more than four years ago, featured an article declaring: ‘Slower economic growth prospects for Brazil, China and India have already spawned a search for the next group of darling countries that will lead the way. A whole new set of acronyms is already starting to emerge. ‘ Fidelity Investment and Jim O’Neill attempted to popularise ‘MINT’ (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey). The influential global website Business Insider declared in January 2014 ‘the BRIC era is over’ and ‘Make way for the MINTs’. But none of these other proposed groups has achieved any lasting traction.

The reason no other acronym has achieved anything like the impact of BRICS is that whether other developing economies grow rapidly or not the reality is they are too small to decisively affect the course of the global economy. For example, in the next five years, even measured in PPPs, the MINT economies on IMF projections will account for only 6.4% of world growth compared to 44.5% for BRICS. Again, therefore, this clarifies that the BRICS economies are not important primarily because they are all fast growing but because they are extremely large – South Africa being the exception because it is de facto included as a representative of the African continent as a whole.

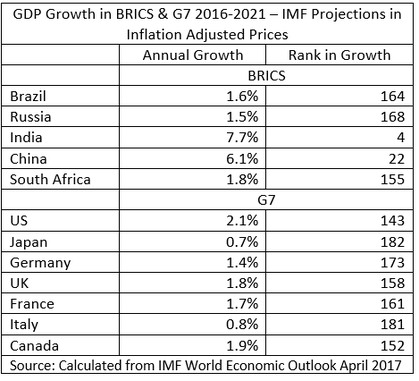

This reality, that it is size of the BRICS economies which is decisive, is even clearer if it is noted that, with the exception of China and India, neither BRICS nor the G7 includes economies projected to be among the world’s most rapidly growing – see Table 1. Of the 192 countries for which the IMF makes growth projections then, leaving aside China and India, the other G7 and BRICS countries rank between 143rd and 182nd of the world’s most rapidly growing economies – that is, towards the bottom of world rankings in terms of rather of growth. Apart from China and India the other BRICS and G7 economies are in the slowest growing quarter of world economies – or put in other terms, leaving aside China and India, three quarters of the world’s economies are growing more rapidly than the G7 or BRICS economies.

The reasons why, due to their erroneous policies, advanced economies cannot accelerate their economic growth is examined in The Great Chess Game (一盘大棋? ——中国新命运解析) and the same reasons apply to those developing BRICS economies which also follow neo-liberal policies.

Therefore, neither BRICS nor G7 are, overall, groupings of very rapidly growing economies. But nevertheless, due to their size, the decisive role of BRICS & G7 combined within the global economy may be seen in the fact that together the account for nearly two thirds of world growth measured in PPPs and over two thirds of world growth measured at current exchange rates.

A more detailed analysis of the respective weight of BRICS and G7, and their role in world growth, will now be given.

World growth

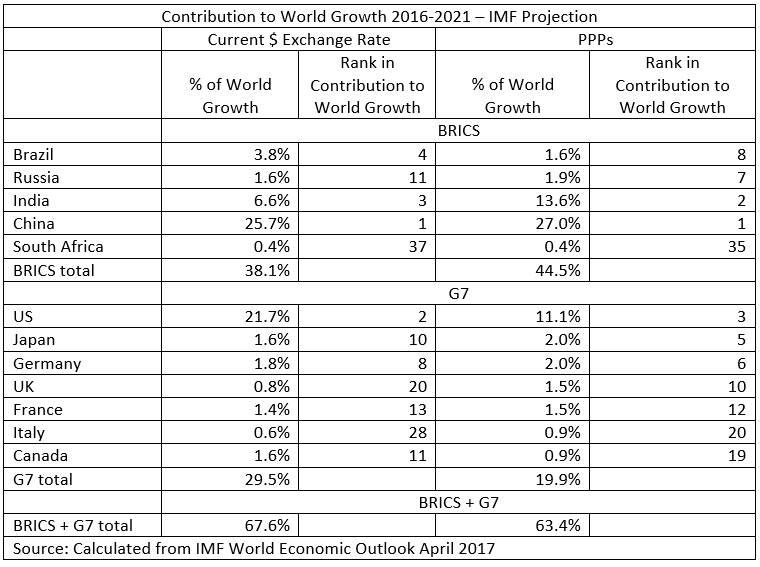

Although both the G7 and BRICS contain very large economies, Table 2 shows clearly that the role of the BRICS economies is much more important for world growth than the G7.

- Measured at current exchange rates, the IMF calculates that BRICS economies will account for 38% of world growth during the five-year period 2016-2011 – compared to 30% for the G7.

- In PPPs, the BRICS economies will account for 45% of world growth and the G7 for 20%.

Therefore, no matter how measured, the BRICS economies are a much more powerful locomotive of world growth than the G7.

It is the fact that the BRICS economies really are very powerful in their effect on world growth that provides the glue for the BRICS grouping.

Policy problems

This reality that both BRICS and G7 are important because of the size of the economies within them,, not primarily because of rapid growth, immediately removes an attempted criticism made of BRICS – that two of its economies, Brazil and Russia, have recently decelerated from earlier faster rates of growth, while South Africa has never had a fast growth rate. It is certainly a problem that Brazil and Russia have both adopted neo-liberal policies. This is in contrast to China and India, which have maintained rapid economic growth due to use of high levels of state investment – see my article ‘Why Are China and India Growing So Fast? State Investment’ ( 全球新常态下 政府投资是中印两国经济快速增长的关键)

Certainly, as always, neo-liberal policies lead to economic failure, particularly in major economies. But it should be noted that the IMF projections for Brazil, Russia and South Africa are already low, implicitly assuming the continuation of the results of neo-liberal policies, and therefore the data on the impact of BRICS on global economic growth given above does not rely on any acceleration in growth by Brazil, Russia or South Africa – the IMF projection for annual average growth in Brazil from 2016-2021 is 1.6%, Russia 1.5%, and South Africa 1.8%. But projections for G7 growth are also in the range 0.7% to 2.1% – essentially in the same range as the slower growing BRICS economies. The much higher growth of BRICS therefore relies on fast growth in China and India, not the situation in the other BRICS economies. The slower growth in Brazil and Russia is a problem for these economies but by itself does not undermine BRICS – as the BRICS economies are held together by the fact that they are the world’s largest developing economies, not the fact that they are extremely rapidly growing.

It is also this large size of the BRICS economies, their scale of contribution to world economic growth, that gives the also gives weight to key initiatives of the BRICS such as the New Development Bank – still better known under its original title of BRICS Development Bank. On this basis BRICS was also able to arrive at satisfactory arrangements for these initiatives – such the New Development Bank being based in China but with its first President coming from India.

Political problems

Another issue for the BRICS is their political outlook. At the time of the creation of the formal structure of BRICS all five countries were headed by parties which might be described as ‘progressive patriotic’. Since then the Presidency of Brazil has been taken by a leader seen as pro-US. However, this has led to no move by Brazil to withdraw from BRICS – the economic interests of the Brazilian state were more powerful than the change in international political orientation of its government.

Of course, a very severe political crisis between BRICS members, for example a violent conflict between China and India over their border issues, would seriously challenge the unity of BRICS. But short of such a very large negative geopolitical event differences between BRICS members will naturally exist but not threaten its unity. Furthermore the differences between G7 members are now also considerable – the last G7 summit say extremely sharp economic differences between the US and Germany, and complete disagreement between the other six members and the US on climate change and the Paris Climate Accord.

The claim by the Financial Times in an editorial five years ago disparaging BRICS on the grounds ‘there is not yet enough mortar in the Brics alliance’ therefore looks rather ironic given the present level of disputes in the G7.

Relations with the G20 and other economies

To avoid any confusion, it should be made clear that the 20 economies for which data is given above are the 20 largest national economies in the world, not the formal grouping the G20 – although the two groups largely overlap in composition. But the reality already analysed of BRICS and G7 in reality clearly defines the two groupings in relation to the formal G20.

- BRICS, in addition to its own structures, is de facto a type of ‘caucus’ of the most important developing countries within the G20 in which common interests of the largest developing economies can be potentially worked out.

- The G7, in addition to its own structures, is a type of caucus of the most important advanced economies within the G20.

These realities, however, obviously raise the question of the relation of members of the formal G20 that are not members of either the G7 or BRICS to those groupings. As the EU, which is a member of the G20, is also invited to attend the G7 meetings this leaves seven national economies in the G20 which are not members of either BRICS or the G7 – Argentina, Australia, Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and Turkey. The projected contribution of these countries to world economic growth is shown in Table 3. It is clear from this data that by far the most important economy which is outside either the BRICS or G7 economies is Indonesia. Indeed, in terms of its contribution to world growth Indonesia is ranked 5th in the world (after China, the US, India, and Brazil) and in PPPs it is ranked 4th (after China, India and the US). In short Indonesia’s contribution to world economic growth is larger than most members of either the G7 or BRICS.

Indonesia is a developing country, and therefore has more in common with the objecive position of the BRICS economies than the G7. Indonesia is a strong participant in the Belt and Road (B&R) initiative, with its president attending the recent B&R summit in Beijing. But it is clear that developing the closest possible relations with Indonesia should be a high priority of BRICS.

Conclusion

The trends analysed above allow an objective examination of various attempts to denigrate BRICS in the Western media which is echoed by some media in China. There are two possible reasons for this type of attack.

- The first is that it represents an intellectual hangover from the days when the West dominated the world, which results in many western so called ‘intellectuals’ or media being unable to see the changes which taken place in the world because they are unable to escape from their old colonialist mentality.

- The second is that BRICS is indeed not important.

The method of ‘seek truth from facts’ settles this issue. No matter how measured the contribution of BRICS to world economic growth in the next five years will be substantially greater than the G7. That is not the view of an ‘anti-Western’ analyst, or an extreme Chinese nationalist, it is the only conclusion which follows from the data of a pillar of Western economic orthodoxy – the IMF. The facts show clearly why, alongside B&R, China is entirely correct to consider BRICS a major part of its strategy.

Naturally the economic projections of the IMF analysed above are ‘broad brush strokes’ ones – examining the main parameters of global economic development. While the fundamental parameters will not change specific features will. Part of the ongoing work on BRICS at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China is therefore to check actual economic trends against these overall projections.

Appendix for economic specialists – a detailed note on IMF growth projections

To avoid the main trends in the global economy being obscured by secondary arguments the economic growth projections of the IMF from the latest database for World Economic Outlook have been used in this article without alteration. It is, however, for economic specialists worth making a comment on the details.

As already analysed above only three countries – China, the US, and India – will account for 54% of world growth measured at current exchange rates and 52% measured in PPPs. No other economy in the G7 and BRICS accounts for more than 2% of world growth by either measure. Therefore, while all G7 and BRICS economies are affected by general synchronised accelerations and decelerations in the world economy, no individual national economy, except China, the US and India, is large enough by itself to make an overall difference to world growth. Only a simultaneous movement in a substantial number of the other nine economies in BRICS and the G7 – i.e. excluding China, the US and India – would make a substantial difference to world growth. Therefore, evaluating the IMF’s growth projections really comes down to two issues:

- Individually examining the growth projections for China, the US and India.

- Seeing if there is any systematic ‘optimism bias’ (exaggeration of growth) or ‘pressimism bias’ (underestimation of growth) across a substantial number of the other BRICS and G7 economies.

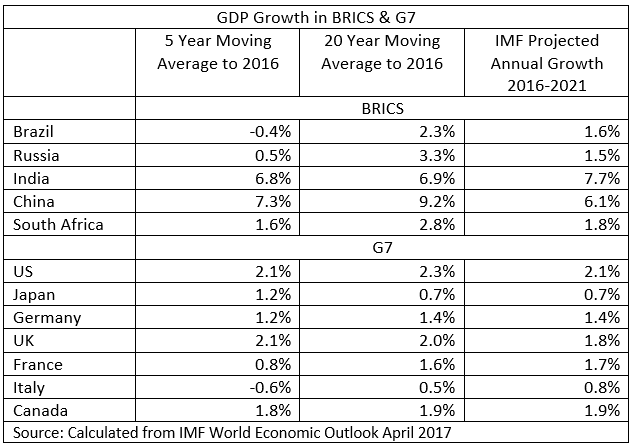

Taking these in order, and using data shown in Table 4:

- US medium/long term is very stable. Annual US average growth measured by a 20-year moving average is 2.3% and measured by a five-year moving average is 2.1%. Therefore, there is no reason to suppose that US actual growth will differ greatly from the 2.1% annual average projected by the IMF.

- The IMF projects China’s annual average growth in 2016-2021 will be 6.1%. This is of course significantly below either China’s 20 year or 5 year annual average growth rates – or the 6.9% so far in 2017, It is notable that in its July update to World Economic Outlook the IMF upgraded its growth projection for China for 2017 by 0.1% to 6.7% and for 2018 by 0.2% to 6.4%. Therefore, the IMF’s 2016-2021 projection for China may be conservative. However, in order to avoid any suggestion data is being manipulated in a way favourable to China, the conservative estimates of the IMF in the April 2017 World Economic Outlook have been used in the calculations above.

- The 7.7% annual average growth projected for India by the IMF is significantly above either India’s 20-year moving average annual growth of 6.9% or its five-year moving average annual growth of 6.8%. The IMF is therefore assuming a significant acceleration in India’s annual average growth rate in 2016-2021 which may or may not occur. However, all data indicates India’s economy will continue to grow fast, and to avoid suggestion of biasing data against India the higher growth rate projected by the IMF has been used in the calculations above – however, it should be noted, that this IMF projection may be somewhat too optimistic.

- Considering the other BRICS and G7 economies this shows no systematic optimism bias or pessimism bias. Projections for Germany and Canada are in line with both 20 year and 5 year moving averages; data for France and Italy is ‘optimistic’ in that it is above both 20 year and 5 year averages for those countries; data for the UK is ‘pessimistic’ in that it is below both 20 year and five year moving averages; data for Japan is ‘moderately pessimistic’ in that it is at the 5 year moving average but below the 20 year movement average, data for Brazil, South Africa, and Russia shows significant differences between 20 year and five year moving averages and IMF projections are between the two. Projections for these individual economies in the G7 and BRICS will doubtless prove too optimistic or pessimistic but, as already noted, each of these economies is too small to individually greatly influence global growth. There is no evidence of a systematic optimism or pessimism bias for these economies taken as a whole.

Therefore, the IMF projections may be taken as reasonable – with the two major identifiable ‘risks’ that could have a substantial effect on world growth being an upside one in the case of China and a downside one in the case of India. Synchronised movements in the world economy would of course affect all economies but would seem unlikely to alter the relative contributions of each to global growth.

More detailed studies of development of individual countries are, of course, as already stated part of the work done on BRICS at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China.