It is a major mistake to believe that the US only made a turn towards protectionism starting with Trump. The US turn towards protectionism already started with Obama’s Transpacific Partnership (TPP) – which was not a ‘free trade’ deal but the attempt to create a protectionist bloc dominated by the US.

Trump is therefore not a break with this turn towards protectionist policies by the US but merely a deepening of them.

These US protectionist trends, which started before Trump, are rooted in the declining weight of the US in the world economy. They leave China as the most important country supporting the international globalised economy. Globalisation has brought immense benefits to developing countries and to developed countries which have not followed neo-liberal policies.

This article analyses the fundamental forces which led the US to shift towards protectionism even before Trump and how China has emerged as the main pillar of globalisation.

Trump is therefore not a break with this turn towards protectionist policies by the US but merely a deepening of them.

These US protectionist trends, which started before Trump, are rooted in the declining weight of the US in the world economy. They leave China as the most important country supporting the international globalised economy. Globalisation has brought immense benefits to developing countries and to developed countries which have not followed neo-liberal policies.

This article analyses the fundamental forces which led the US to shift towards protectionism even before Trump and how China has emerged as the main pillar of globalisation.

* * *

On 15 February 2016 Obama held a summit with ASEAN leaders in California. While no major concrete agreements were projected to come from the meeting it represented an ongoing part of a US policy aiming to draw some Asian countries into protectionist economic agreements with the US – the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) being the clearest example of this. Therefore, the California summit was most clearly understood as part of a longer term ongoing process whereby China has become the main support of an open and multilateral global economic order whereas, due to the relative decline of its weight in the global economy, the US is shifting towards unilateral and protectionist policies.

A further example of this process was that the beginning of 2016 changes in the structure of the IMF at last came into effect which had been originally agreed in December 2010 under the impact of the international financial crisis. They gave China the third largest place among IMF quotas and meant the BRIC economies (Brazil, China, India, and Russia) became among the 10 largest members of the IMF – joining the US, Japan, Germany, France, the UK and Italy. More than six percent of quota shares were shifted to developing economics.

The reason for the prolonged five-year delay in implementing these necessary changes, reflecting the growing economic weight of developing countries, was that until the end of 2015 the US Congress refused to pass legislation to implement agreements already negotiated by the US government.

It is clear what persuaded Congress to change its position. It was China’s success in setting up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the refusal of key US allies, such as Britain, to go along with US government calls to boycott the AIIB. This made clear that if the US continued to block necessary reforms in existing international economic institutions China had the strength to create alternatives and other countries would not endorse US inflexibility.

The delayed change in the IMF illustrates China’s overall approach to global economic governance. China clearly had not sought confrontation or attempted to bypass existing global institutions for no valid reason – on the contrary China showed considerably patience confronted with prolonged foot- dragging by the US legislature. Also the AIIB from the outset was open to all countries. China showed the same patience in the rather lengthy process by which the RMB was included in the IMF’s basket of currencies for Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). These cases confirm China is pursuing a path of preferring to gradually and organically adapt multilateral economic institutions to take account of major shifts in the world economy and only being forced to go outside existing institutions if evidently required changes are entirely blocked.

In contrast the US has recently initiated a new foreign policy path of going outside existing global economic organisations in a confrontational fashion – as seen clearly with international trade. When the World Trade Organisation (WTO) was created in 1995 this was the culmination of seven previous rounds of post-World War II trade negotiations under the earlier General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade agreements (GATT). For half a century the US had played a leading role in negotiating such multilateral agreements.

With the emergence of China as the world’s largest goods trading organisation, second only to the US in total trade, the most important multilateral negotiations to further liberalise world trade should clearly involve the US, China and the EU – the three main world trade centres. But instead of pursuing multilateral liberalisation, centring on the WTO, the US instead sought negotiations excluding China – seeking to arrive at agreements with some Pacific countries via the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) and with Europe in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Therefore, whereas China pursued a strategy of maintaining and developing the framework of exiting multilateral organisations, except in the case where change in these is entirely blocked, the US deliberately initiated a process going outside them.

The contrast is still clearer if the content of Obama’s proposed TPP is examined. Instead of being based on the most dynamic sectors of the world economy, which would include China, the TPP is an agreement between a group of economies declining in global economic weight – in 1985 economies in the proposed TPP accounted for 54 percent of world GDP while by 2014 this had dropped to 36 percent.

The TPPs main mechanisms are aimed at protecting the position of the US and its companies. Under the TPP private companies, principally US ones, would have the right under to sue participating governments in courts which will be dominated by the US but whose decisions are binding on national governments.

In contrast to the narrow TPP China has advocated a wider multilateral Asia-Pacific Free Trade Agreement. Therefore, in trade, as the with IMF reform, China has been pursuing a multilateral approach whereas the US has made a turn from earlier post-World War II support for multilateral agreements and organisations to unilaterally pursuing specifically US interests. As most other countries benefit greatly from a multilateral approach, in which they also have a role to play in negotiations, why is there now this contrast in approach between China and the US and will it continue?

The US turn is clearly in line with that advocated in ‘Revising US Grand Strategy Towards China’ a policy paper published by the prestigious US Council on Foreign relations. This argued bluntly that the US should create: ‘new trade arrangements in Asia that exclude China.’ Instead the US should seek for: ‘creating new preferential trading arrangements among US friends and allies to increase their mutual gains through instruments that consciously exclude China.’

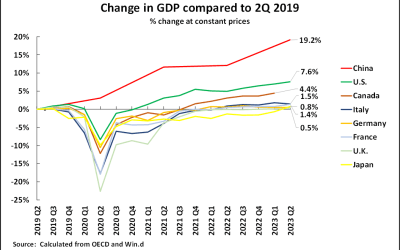

The reason for this shift is clear. Contrary to the myth the US promotes that it is a uniquely ‘dynamic’ economy the reality is the US economy has been slowing and its weight in the global economy declining. From 1984-2014 the US share of world GDP fell from 34 percent to 23 percent at current exchange rates. Taking a 20- year moving average, to eliminate the effects of short term business cycle fluctuations, average US GDP growth fell from 4.4 percent in the late 1960s to 2.4 percent by 2015.

Therefore, as Philip Stephens of the Financial Times summarised US goals: ‘China has been the big winner from the open global economy.’ The result is that the US: ‘has given up on the grand multilateralism that defined the postwar era.’

In summary, these economic trends explain and will strengthen the recent pattern whereby China has become the main pillar of adapting and extending existing global multilateral economic governance institutions while the US makes a turn towards adopting a unilateral approach.

* * *

The original version of this article appeared in Chinese at Sina Finance Opinion Leaders on 15 February 2016. A new introduction has been added but, apart from changing the article to the past tense, and referring to Trump’s victory, no changes have been made to the original.

Related articles

The end of US neo-liberalism – the meaning of Biden’s change in US economic policy

In the US President Biden is carrying out a revolution in economic policy which, without openly acknowledging it, ...

Read More Trump’s economy – cyclical upturn and long term slow growth

It is crucial for China’s perspectives, both economically and geopolitically, to have an accurate analysis of the trends ...

Read More The news is full of headlines about ‘China’s economic collapse’ — ignore them

Once again, the Western media Establishment, and sadly some on the left, are talking up an impending economic ...

Read More The new shape of world politics – disorder in the West, stability in the East

The following article on 'The New Shape of World Politics - Disorder in the West, Stability in the ...

Read More A Copernican Revolution in Western economics & China’s supply side reform

Every 4th May is National Youth Day in China. In 2016 I was invited on that day to deliver a lecture to ...

Read More